Agonizing over having to lay off valued employees? Well, you may not need to.

April 9, 2020

Vlog – How to Define Your Value Proposition

May 18, 2020Technology Is Not Logical, But Deeply Emotional

In 2004, psychology and social computing professors John McCarthy and Peter Wright challenged us to think about “technology as an experience” rather than merely a product that is used. Never has this been more evident than during the past few months of worldwide lockdown. Getting food, educating children, working, keeping businesses afloat, and maintaining relationships with friends and family have only been possible by leveraging technology. Never have we been so vulnerable and dependent on technology to do everything.

We love technology, right? Or do we loathe it? Mostly, we appreciate it—when it works, when it improves our lives or helps us do our job. Yet, we fear it when it threatens our jobs, and we want to throw it out the window in anger when it doesn’t do what it is supposed to or delivers heartbreaking news. The critical realization, as McCarthy and Wright (2004) tried to tell us years ago, is that we are not passive or neutral users of technology. We co-exist with technology; we live with technology. It has become an intimate part of our working and personal lives without us even being conscious of this infiltration.

Technology vendors invest many years and capital into building better, more innovative apps and devices designed to make our lives better by saving us time, increasing our effectiveness, and making us more productive. But we don’t often think about the experiences our buyers have with the technology we create and sell, beyond design considerations. Buyers have a personal relationship with our technology, and a range of emotions are triggered by each engagement. Two users can view the same technology from polarized perspectives. A new iPhone X can be a status symbol, triggering pride and satisfaction with each use. Yet, on a busy train ride to work, that same phone might be an annoyance and social disturbance. When lost in a dark alley in a foreign city, it can feel like a lifesaver; or, it might stimulate panic, fear, anger, and helplessness should the battery die. We curse the device for abandoning us in our time of need.

The truth is, we don’t use technology—it uses us. It has woven its way into every aspect of our daily lives. We have a personal and intimate relationship with it, and it has more power in the relationship than we do. My daughter yells at me if I threaten to take her phone away; my son gets angry when it’s dinner time and says he can’t leave his computer game or will be kicked out. This is not a neutral, rational relationship with technology. This is a deeply emotional relationship. During the pandemic, we taught my 80-year-old mother how to use WhatsApp. Now, each morning, she is happy knowing her kids are OK, and she sleeps better having said goodnight to her children living across the world. The device is her comfort, her sense of safety in the world, and a reprieve from her fear and loneliness, nestled on her nightstand. A simple 5-word text from a person in another country has the power to stimulate feelings of peace and connection or sadness and despair.

Technology may appear to be a logical, rational, neutral, and mechanistic device or program with processes, algorithms, and bits and bytes. But anyone who has wanted to smash their laptop or has slammed their first down on their desk out of frustration knows that technology has crept into our very being. We do not simply use it; it affects us and impacts our emotions and states of being, whether we realize it or not.

I believe marketers have become conditioned to promoting and marketing technology in a rational, logical way. 30 years ago, marketing was designed to educate and teach. Today RFPs contain many logical decision criteria, brochures have lists of features and functionality, product demos show fields, screenshots, and dashboards. Where is the acknowledgment that choosing and using technology is not a neutral, logical, and rational decision? Where are the people with emotions on technology provider websites? Where are the humans in this dance with technology?

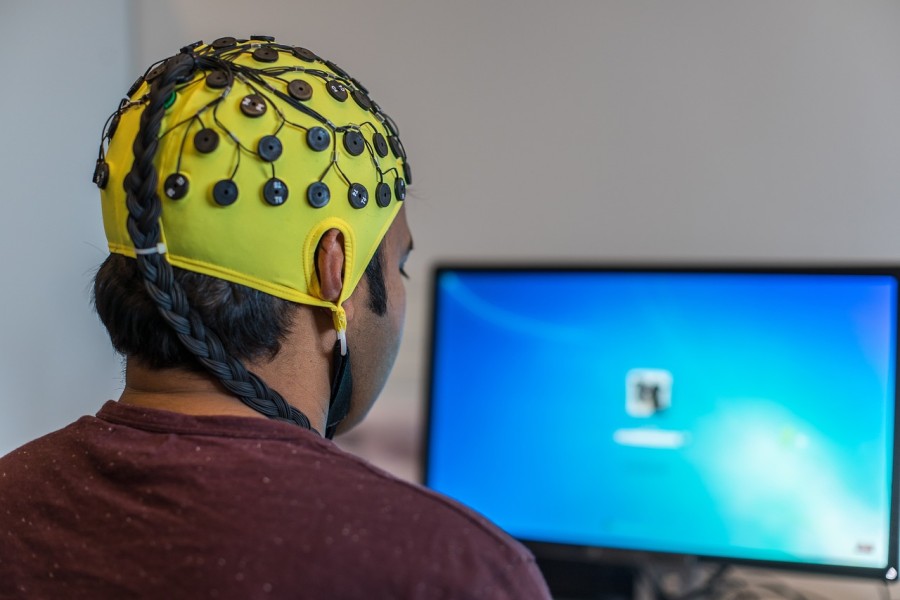

There are also emotional implications related to the design of technology. We can no longer sit in our offices and brainstorm the design of new solutions. We need to go out into our customer’s world and observe their use of our technology—in their context—to witness their ups and downs as they interact with and experience our offerings. As Winograd and Flores (1986) suggested, using an ethnographic approach can be extremely helpful. This observation approach allows designers to discover the unique cultures, habits, and experiences of their users. As Winograd and Flores further stated, we need to move away from understanding technology as cognitive (augmenting the knowledge and supporting decision-making) and instead move toward technology as participating in the kinds of actions that make up our lives.

Technology affects and enables our daily experiences at home and work. We wake to our phone alarm, we scan the daily news on our app, we text with our loved ones and relax with Netflix in the evening. This relationship is ever-present and an integral part of our lives. At times we are oblivious to this interdependency and only pay attention when the technology sets off our emotions. Data gathered by a CRM system can lead to an individual’s promotion or termination. A software glitch can lead to a massive error, costing a company millions, but it can just as easily save the company millions by reducing human error. Technology can include or exclude, reward, or punish. My son went traveling after university and committed to a social media detox—his friends were angry and hurt and shunned him. Our love-hate but ever-present relationship with technology persists, and we are so conflicted. Parents fear their kids getting addicted to computer games yet feel guilty for being grateful that it occupies their time for a few hours of reprieve. Sales professionals love that they can see a real-time view of their monthly commissions but hate that the manager can see they are having a bad month.

I think we need to conduct more research and engage in more discourse about our emotions toward technology and this very personal, conflicted relationship we have with it. At the very least, as the evangelists of the incredible potential of digital transformation, we could benefit by shifting our sales and marketing narrative from speaking about technology as a product we passively buy and use and instead explore how our customers are leveraging and engaging with it. To celebrate the incredible positive impacts and benefits while acknowledging and embracing the human challenges, fears, uncertainties, and frustrations that accompany it. An authentic, empathetic dialogue is required, not a sales pitch.

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

References:

McCarthy, J. and Wright, P. (2004). Technology as Experience. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Winograd, T. and Flores, F. (1986) Understanding Computers and Cognition. Ablex Publishing Corp. Pg. 207.